I recently consulted on a project where a system failure was traced back to an underestimated pressure rating. This experience shows why understanding the true limits of a valve is non-negotiable for system safety.

The maximum pressure rating for a standard PEX-AL-PEX 121UC valve is typically PN16, which means a nominal working pressure of 16 bar (approximately 232 psi) at a reference temperature of 20°C (68°F). This rating is crucial, but it is just the starting point for a complete engineering assessment. In fact, the actual allowable pressure depends heavily on the operating temperature and relevant safety standards.

Pressure rating is a system’s license to operate safely. Therefore, let’s examine what PN16 really means and explore the critical factors that determine safe, long-term performance.

What is the PN Rating or Working Pressure in Bar at 20°C and 95°C?

Clients often see a PN number and assume it applies universally. However, this is a common and dangerous misunderstanding I help clarify.

At 20°C, the working pressure is the PN rating, typically 16 bar for a PN16 valve. However, at 95°C, the maximum allowable operating pressure drops significantly. It often falls to around 6-7 bar for continuous operation, due to the reduced strength of polymer materials at high temperatures. International standards like ISO 21003 define this derating.

Decoding the PN Rating

The PN (Pressure Nominal) rating is a standardized classification. PN16 means the component is designed for a maximum working pressure of 16 bar at a reference temperature of 20°C. This is not a burst pressure, but a safe, continuous operating limit under ideal, cool conditions.

It is essential to understand that this rating applies to the entire assembly. For example, it covers the valve body, its internal mechanisms, and its connection points. In PEX-AL-PEX systems, the valve is often the limiting component, so its rating governs the entire system.

The Critical Impact of High Temperature

Plastic materials, including the PEX layers in PEX-AL-PEX, lose mechanical strength as temperature increases. Therefore, the safe working pressure must decrease to compensate and ensure long-term reliability. This relationship is not optional; standards actually prescribe it.

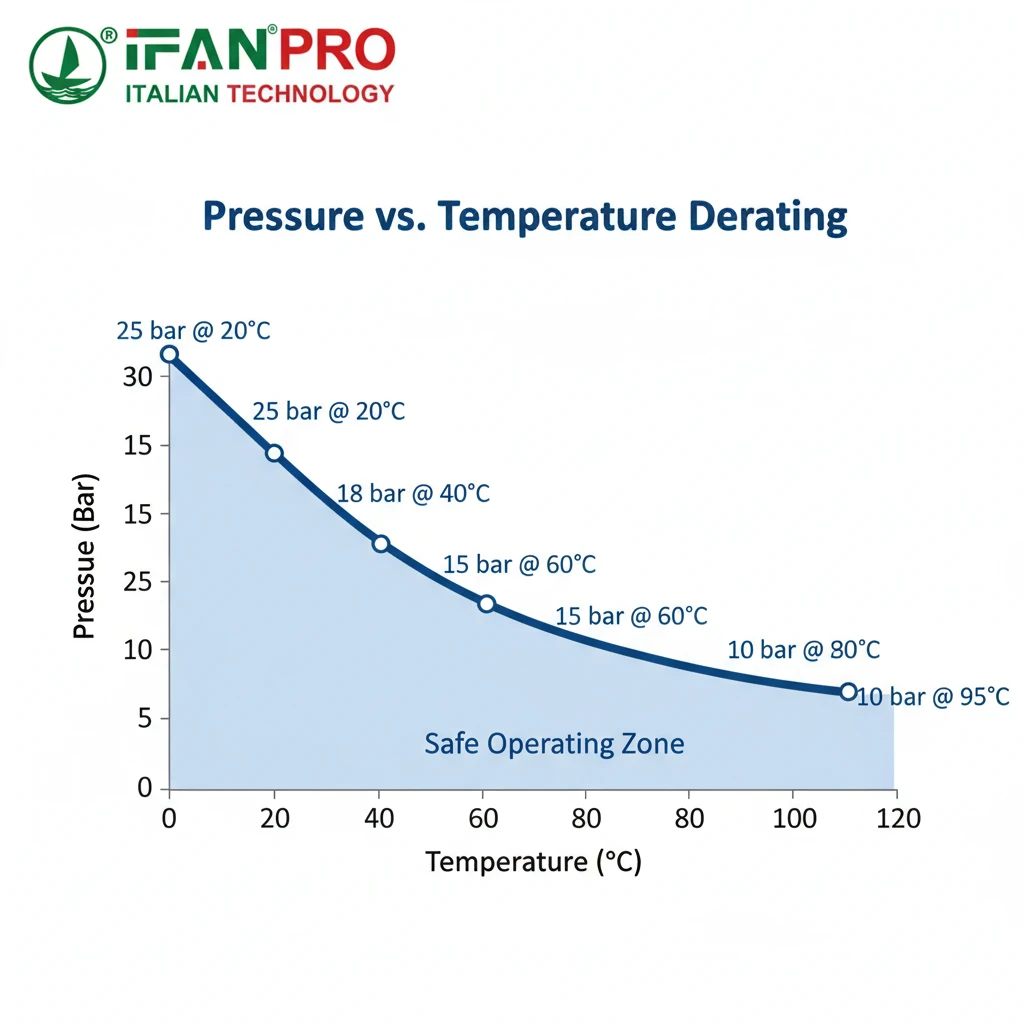

A standard PN16 PEX-AL-PEX valve follows a pressure derating curve like the one described in ISO 21003. Here is a simplified table showing typical allowable pressures at key temperatures:

| Operating Temperature | Maximum Allowable Working Pressure (for PN16 Valve) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 20°C (68°F) | 16.0 bar (232 psi) | Reference condition for the PN rating. |

| 60°C (140°F) | ~10.0 bar (145 psi) | Common for domestic hot water systems. |

| 82°C (180°F) | ~7.5 bar (109 psi) | Often used for space heating applications. |

| 95°C (203°F) | ~6.5 bar (94 psi) | Typical maximum continuous temperature limit. |

This derating is the most critical practical takeaway. For instance, installing a PN16 valve in a 95°C system and expecting it to hold 16 bar is a fundamental error that will lead to premature failure. Consequently, you should always check the manufacturer’s specific pressure-temperature charts.

How Does Temperature Affect the Maximum Allowable Operating Pressure?

Temperature is the primary enemy of long-term pressure capacity. I’ve seen too many systems designed with only cold water pressure in mind, leading to callbacks and leaks.

Temperature inversely affects the maximum allowable pressure because heat weakens the plastic components (PEX layers) of the valve. As temperature rises, the polymer chains become more flexible and less resistant to internal stress. This forces a reduction in the system’s operating pressure to prevent creep deformation and ensure a 50-year service life.

The Science Behind the Strength Loss

The PEX (cross-linked polyethylene) in the valve body and seals is a thermoplastic polymer. Its strength comes from the chemical bonds (cross-links) between its molecular chains. When you apply heat, you add energy to these molecules.

This increased energy makes the chains vibrate more and slip more easily past each other. While the cross-links prevent melting, they cannot stop this softening. This means that under constant pressure at a high temperature, the material can slowly and permanently deform—a process called “creep.” To prevent creep failure over decades, standards mandate lowering the applied stress (pressure) as the temperature rises.

Practical Consequences for System Design

This relationship dictates everything in system engineering:

- System Classification: You must design for the highest constant temperature the system will see, not the average. For example, a solar thermal loop or a central heating boiler line often dictates the derating for the entire related subsystem.

- Safety Device Calibration: Pressure relief valves (PRVs) must be set based on the derated pressure at the operating temperature. A PRV set at 12 bar in a 95°C system with a valve rated for 6.5 bar at that temperature is useless. In fact, the valve could fail before the PRV activates.

- Intermittent vs. Continuous Heat: Some standards allow for slightly higher pressures if the high temperature is intermittent (e.g., a few hours per day). However, for safety and simplicity, most engineers design for continuous temperature exposure.

The Role of the Aluminum Layer

In the PEX-AL-PEX pipe, the aluminum layer provides excellent strength. However, for the valve, the internal mechanisms and sealing surfaces are primarily polymer-based. Therefore, the aluminum reinforcement in the connected pipe does not increase the pressure rating of the valve itself. Ultimately, the valve remains the critical component limiting the system at high temperatures.

What Safety Factor is Applied to the Valve’s Pressure Rating?

The PN rating is for working pressure, but what about unexpected surges? This is where the hidden safety factor comes in, and it’s a key detail we always verify.

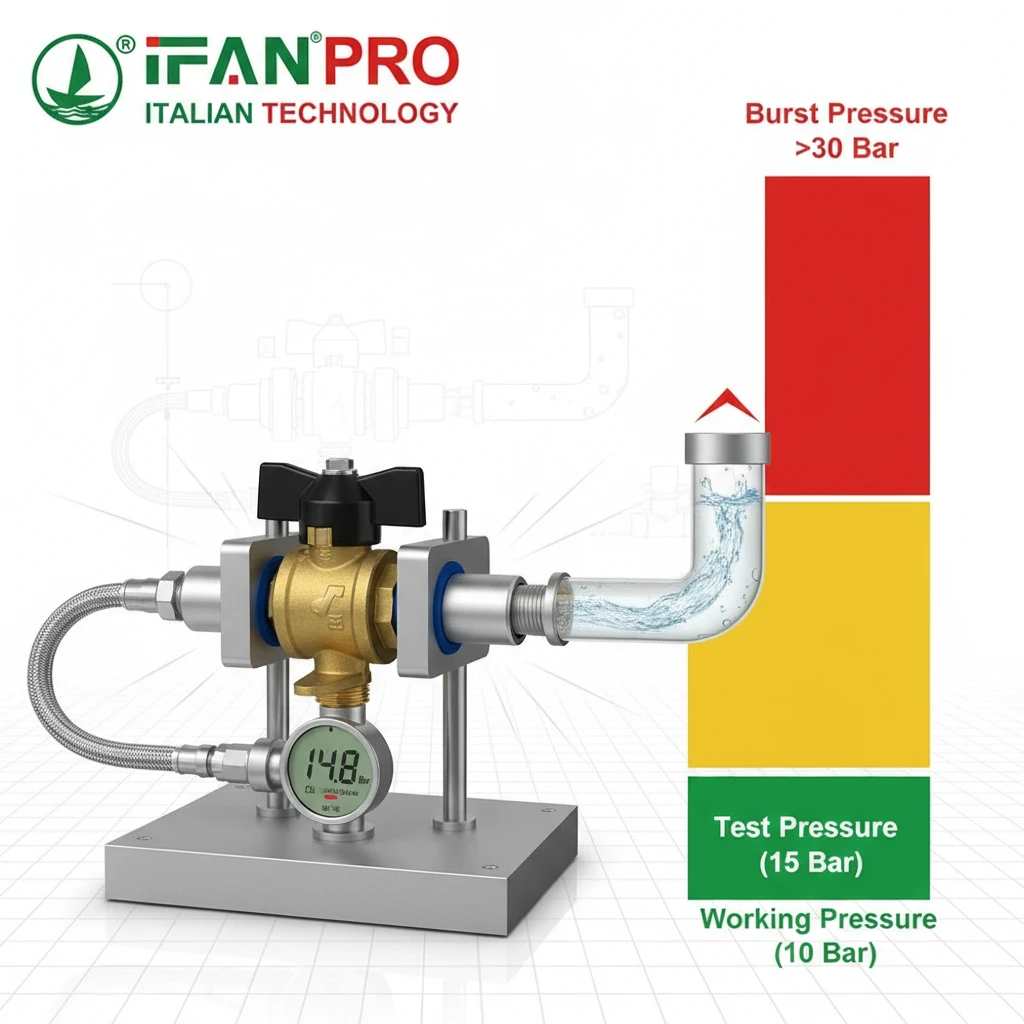

A significant safety factor is applied between the valve’s working pressure (PN) and its minimum burst pressure. According to standards like ISO 21003, components must withstand a pressure test at a multiple of their PN rating (e.g., 1.5 x PN at 20°C) for a short period. Additionally, they must have a much higher ultimate burst pressure, typically ensuring a safety factor of 2.5 to 4 against catastrophic failure under normal conditions.

Understanding the Layers of Safety

The safety factor is not a single number but a built-in engineering margin applied at different stages. It accounts for material variances, installation stresses, and unexpected pressure spikes (water hammer).

Here’s how it typically works for a PN16 valve:

- Hydrostatic Test Pressure (Short-Term): During factory testing, valves must withstand a pressure of 1.5 x PN (24 bar for PN16) at 20°C for a short time (e.g., 1 hour) without leaking or deforming. Engineers use this as a quality control test, not a recommended operating condition.

- Burst Pressure (Ultimate Failure): The actual pressure required to cause a rupture is much higher. For a quality PN16 valve, the minimum burst pressure at 20°C is often 4 x PN (64 bar) or more. This margin provides the ultimate safety margin.

Calculating the Effective Safety Factor

We can express this as a practical safety factor (SF):

SF = Minimum Burst Pressure / Maximum Working Pressure

For a PN16 valve with a 64 bar burst pressure: SF = 64 bar / 16 bar = 4.0

This means at 20°C, the valve has a 4x safety factor against bursting. However, this factor changes with temperature.

How Temperature Changes the Safety Factor

It is crucial to understand that we calculate the safety factor at a specific temperature. The burst pressure also decreases with heat.

| Temperature | Working Pressure (Max) | Estimated Burst Pressure | Practical Safety Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20°C | 16.0 bar | ~64 bar | 4.0 |

| 95°C | 6.5 bar | ~26 bar | 4.0 |

The key insight is that a well-designed valve maintains a constant safety factor across its temperature range. In other words, the working pressure drops to ensure that even at 95°C, the component is still 4 times stronger than it needs to be for normal operation. This is why following the pressure-temperature derating is fundamental to maintaining designed safety.

Is the Rating Certified for Continuous Operation or Only for Peak Conditions?

This question separates quality components from substandard ones. We insist on certifications that prove long-term reliability, not just momentary strength.

The PN rating for valves from reputable manufacturers like IFAN is certified for continuous, 50-year operation at the specified pressure-temperature conditions. This certification is based on long-term hydrostatic strength (LTHS) testing per ISO 9080. This test extrapolates data from thousands of hours of testing to predict a 50-year lifespan, not on short-term burst tests.

Continuous Rating vs. Peak Rating: A Vital Difference

- Continuous Operating Rating: This is the true mark of quality. It means the valve can handle the stated pressure at the stated temperature 24/7 for its entire 50-year design life without significant creep or loss of performance. Standards like EN ISO 21003 and certifications like KIWA or DVGW define this.

- Peak or Transient Rating: Some low-quality products may only be tested to hold a pressure for minutes or hours. They might “work” initially at higher pressures but will deform and fail prematurely. As a result, they lack the long-term certification.

The Proof: Long-Term Hydrostatic Strength Testing

How can a manufacturer claim a 50-year rating? The answer lies in rigorous, standardized testing. Laboratories perform the LTHS test:

- Multiple samples are placed in water baths at constant, elevated temperatures (e.g., 95°C).

- They subject the samples to various constant internal pressures.

- Engineers record the time until each sample fails (ruptures).

- Using statistical extrapolation (like the ISO 9080 standard method), they plot a stress vs. time-to-failure curve. This curve reliably predicts the maximum constant stress (pressure) the material can withstand for 50 years (438,000 hours) at that temperature.

This scientific extrapolation is the basis for the pressure-temperature ratings in standards. Ultimately, it is not a guess.

Certifications to Look For

To ensure you are getting a valve rated for continuous operation, demand proof of third-party certification. These bodies audit the manufacturer’s testing and quality controls.

| Certification Body | What it Certifies | Key Region |

|---|---|---|

| DVGW | Conformity with German standards for gas and water. It requires rigorous LTHS validation. | Europe, Global Benchmark |

| KIWA | Approval for drinking water systems under Dutch and European regulations. | Europe |

| NSF/ANSI 61 | Ensures the product does not leach contaminants into drinking water. | North America, Global |

| WRAS | Approval for compliance with UK Water Regulations. | United Kingdom |

A valve bearing these marks has proven its long-term performance. Conversely, a product with no such certification may have a “paper rating” but no verified history of sustained reliability.

Conclusión

Always select a valve based on its certified continuous pressure rating at your system’s maximum operating temperature. For reliable, fully certified PEX-AL-PEX 121UC valves with clear pressure-temperature ratings, specify IFAN para su proyecto.

Comentarios recientes