We once had a client whose high-tech sensor failed during a holiday, flooding a warehouse. This costly disaster made me truly respect the timeless reliability of simple mechanisms.

Choose a mechanical float valve for critical level control because it works with 100% reliability without any power, complex wiring, or software. Its simple on/off mechanism is far less likely to fail due to humidity, power surges, or mineral deposits, making it a robust, low-maintenance, and universally dependable solution.

If you think newer technology is always better, the humble float valve might change your mind. Let’s compare its straightforward power to the potential pitfalls of electronic systems.

How Does a Mechanical Float Valve Achieve Higher Reliability with No Power?

When power fails, electronic controls go blind. I’ve seen too many “smart” systems become useless during an outage, while float valves just keep working.

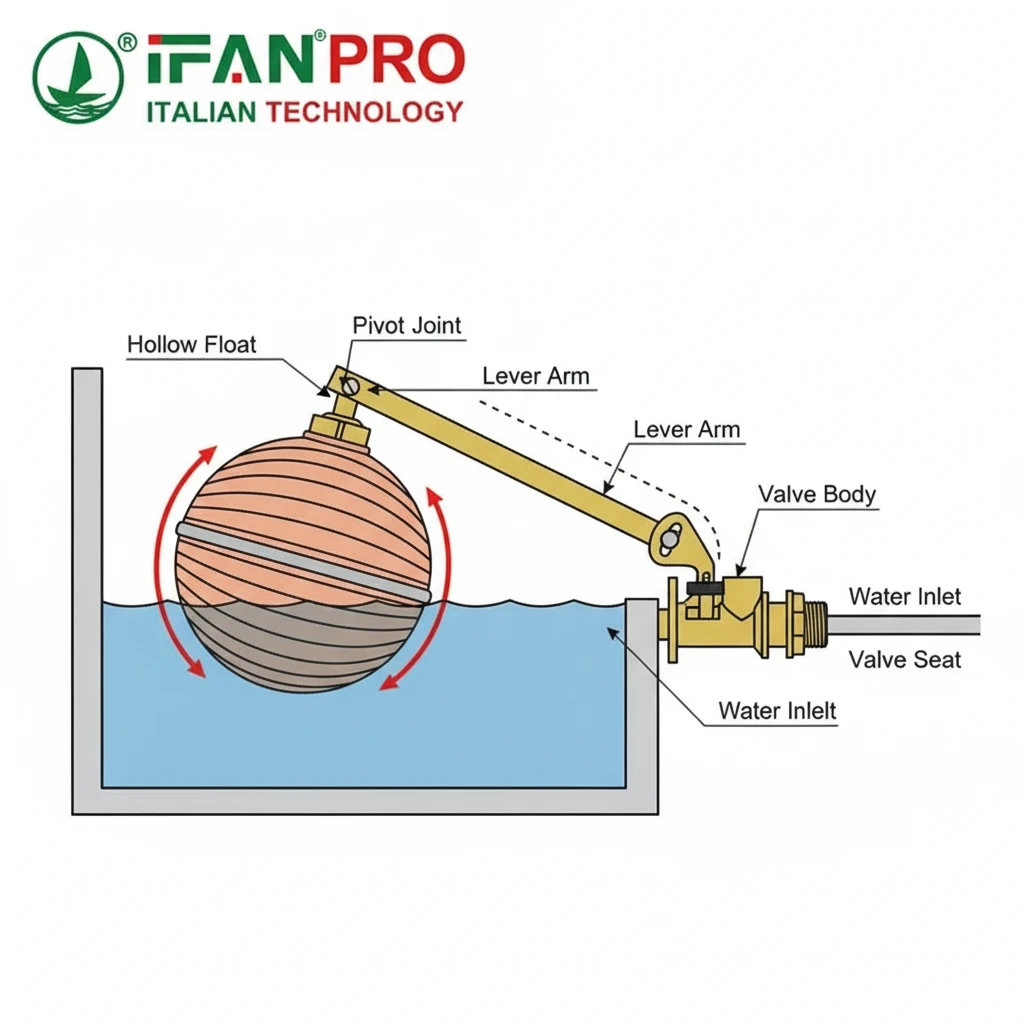

A mechanical float valve achieves higher reliability with no power by using direct physical principles: buoyancy and leverage. As the liquid level rises, the float lifts, mechanically closing a valve via a lever arm. This failsafe, direct-action design has no circuits to short, no software to crash, and no power supply to fail.

The Beauty of Simple Physics

The core reason for its reliability is simplicity. An electronic sensor is a system with many points of potential failure. It needs power, a sensing element, a circuit board, a transmitter, and often a programmed controller. If any one part fails, the whole system fails.

A float valve is just a few parts: a float, a lever arm, and a valve seat. The physics are direct and unavoidable. The float must rise with the water level. The lever must pivot. This motion must close the valve. There is no “interpretation” or signal conversion. This direct mechanical action is incredibly hard to disrupt.

Key Failure Points Comparison

Let’s look at where things can go wrong. The table below compares the reliability of both systems.

| System Component | Float Valve Failure Risk | Electronic Sensor Failure Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Power Dependency | Zero. Fully mechanical. | High. Needs constant, clean power. Power surges or outages stop it. |

| Control Logic | Physical linkage. Always works. | Microprocessor and software. Can freeze or need rebooting. |

| Environmental Damage | Resistant. Only moving part is a pivot. | Sensitive. Humidity, dust, and condensation can damage electronics. |

| Long-Term Wear | Very slow. Only the valve seal wears and is easy to replace. | Multiple points: sensor fouling, wire corrosion, component aging. |

The “Set-and-Forget” Advantage

This simplicity translates to what I call “set-and-forget” reliability. Once you set the float valve to the desired level by adjusting the float or lever, it will maintain that level for years. There are no calibrations to drift, no software updates to install, and no sensitivity settings to adjust. For example, in a rural water tower or a factory coolant tank, installers can set it and be confident it will work without any further attention. This is why they are the undisputed choice for safety-critical applications like toilet tanks and heating system expansion tanks—where failure is simply not an option. Their reliability isn’t a feature; it’s the result of a fundamental, physics-based design.

What Are the Installation and Maintenance Advantages Over Electronic Systems?

Installing complex electronics in damp, dirty industrial spaces is a challenge. I recall a project where just wiring the sensors took longer than plumbing the entire float valve system.

Float valves have major installation and maintenance advantages because they need no electrical conduits, no control panels, and no programming. Installation is simple plumbing. Maintenance involves only occasional cleaning or seal replacement, avoiding costly specialist technicians for diagnostics and sensor recalibration.

Streamlined Installation Process

Think about the installation steps for each system. For an electronic liquid level control system, you must first install the sensor in the tank. Then, you have to run electrical conduit and wires from the sensor back to a control panel, which also needs power. Next, you must program the controller with setpoints (high level, low level). Finally, you connect it to a separate, electrically-actuated valve. This is a multi-trade job requiring an electrician and a programmer, not just a plumber.

Now, look at a float valve. You install it into the tank’s inlet port—that’s it. The valve, sensor (the float), and actuator (the lever) are one single, pre-assembled unit. There are no wires, no separate controllers, and no programming. A single technician with basic plumbing skills can complete the job quickly.

Long-Term Maintenance Simplicity

The maintenance difference is even more pronounced. Electronic systems require regular checks. Sensors can drift from their calibration and need to be re-calibrated with special tools. Control software might need updates. Corrosion on electrical contacts needs to be cleaned.

Maintaining a float valve is straightforward. Over many years, the only part that might wear is the rubber or plastic washer in the valve seat. Maintenance involves:

- Shutting off the water supply.

- Unscrewing a few parts.

- Replacing the inexpensive seal.

- Reassembling it.

No diagnostics, no laptops, and no special training are needed. This is a huge cost saver over the life of the equipment.

Total Cost of Ownership Breakdown

The real advantage becomes clear when you look at the total cost over 10 years.

| Cost Category | Float Valve System | Electronic Sensor System |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Hardware Cost | Low. One integrated unit. | High. Sensor, controller, wired valve, enclosure. |

| Installation Labor Cost | Low. Plumbing work only. | High. Requires electrician and programmer. |

| Annual Maintenance Cost | Very Low. Visual inspection. | Moderate to High. Calibration, software, part replacement. |

| Repair Specialist Needed | General plumber or mechanic. | Electronics technician or system integrator. |

| Risk of Obsolescence | None. Technology is timeless. | High. Controller or software may become outdated. |

For facilities without a dedicated electrical maintenance team, the float valve is not just an option; it is the only practical choice. It keeps the system running and keeps operational costs predictable and low.

Why Is It Less Susceptible to Failure from Humidity or Mineral Deposits?

Harsh environments destroy electronics. We replaced many corroded sensors in a fertilizer plant before the client finally switched to durable float valves.

Float valves are less susceptible to failure because their mechanism is large, simple, and mechanical. Humidity cannot short-circuit a lever arm, and mineral deposits might slow the float but rarely stop it. Electronic sensors, with tiny sensitive circuits and small probe openings, are easily clogged or corroded by the same conditions.

The Problem with Sensitive Electronics

Electronic sensors are engineered for precision, not necessarily for toughness. They fail in damp and dirty environments for specific reasons. First, humidity and condensation can seep into housings, causing circuit boards to corrode and short-circuit. Even sensors rated as “waterproof” can eventually fail if seals degrade.

Second, many electronic sensors, like conductance probes or optical sensors, have small openings or sensing surfaces. Minerals in hard water (like lime scale), silt, algae, or other debris can coat these surfaces. When a conductivity probe gets coated, it can’t sense the water properly. An optical sensor’s lens becomes dirty and gives false readings. Cleaning them is often a delicate, necessary task.

How Float Valves Resist These Issues

The float valve’s design inherently fights these problems. Its operating parts are large and robust. Humidity has no effect on a stainless steel lever or a plastic float. There are no electrical signals to interfere with.

As for mineral deposits or debris: while deposits can form on the float and lever, this usually happens very slowly. Even a heavily scaled float valve will often continue to work—the float might be heavier, but it will still rise and fall. If performance is affected, maintenance is simple: physically clean the float and lever. You can scrub them, chip off scale, or use a mild acid wash without fear of damaging delicate electronics.

Environmental Durability Comparison

Here is how the two systems handle common industrial and environmental challenges:

| Environmental Challenge | Effect on Float Valve | Effect on Electronic Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| High Humidity / Condensation | No effect. Mechanical parts are immune. | High risk. Causes internal corrosion and circuit failure. |

| Mineral Scale Buildup | Low impact. May slow movement but rarely jams. Cleanable. | High impact. Coats sensing element, causing false readings or failure. |

| Dust & Dirt | Low impact. Large moving parts are not easily jammed by debris. | Moderate/High impact. Can clog small openings or interfere with signals. |

| Chemical Fumes | Resistant. Use chemical-resistant materials (e.g., PVC, stainless). | Vulnerable. Fumes can corrode metal housings and damage internal components. |

In applications like agricultural water troughs, livestock tanks, or industrial sumps where water is dirty and the air is damp, the float valve’s resistance is a decisive advantage. It works in the real world, not just in a clean laboratory setting.

In What Remote or Off-Grid Locations Are Float Valves the Only Practical Option?

In off-grid projects, complexity is the enemy. We supplied float valves for a mountain community’s water system where bringing in stable power for sensors was impossible and too expensive.

Float valves are the only practical option in remote or off-grid locations because they operate entirely without electricity. They are perfect for remote water tanks, agricultural irrigation, livestock watering in pastures, and emergency backup systems where power is unavailable, unreliable, or too costly to install and maintain.

The Core Challenge: No Power

The defining feature of a remote location is the lack of reliable infrastructure. Running electrical power lines to a remote stock tank, a forestry station, or a desert outpost is prohibitively expensive. Even if you use solar power, an electronic system adds layers of complexity: you need solar panels, charge controllers, batteries, and inverters, all of which can fail. A float valve bypasses this entire problem.

It is a self-contained, autonomous control system. It uses the energy from the flowing water itself and the buoyancy of the float to operate. As long as there is water pressure to close against, it works.

Key Application Scenarios

Let’s look at specific places where float valves are not just the best choice, but often the only choice.

1. Agricultural and Livestock Watering: This is a classic example. Water troughs in the middle of fields or pastures are far from barns and power sources. A float valve connected to a main water line ensures animals always have fresh water without any risk of overflow or the farmer needing to manually check and fill tanks daily.

2. Remote Cabins and Off-Grid Homes: Many cabins use gravity-fed water from a spring or a hilltop storage tank. A float valve in the storage tank reliably controls the fill from the source, ensuring the tank never runs dry or overflows, all without a single watt of electricity.

3. Disaster Relief and Emergency Water Storage: In temporary camps or emergency water bladders, simplicity and reliability are paramount. Float valves provide automatic level control for drinking water storage without depending on scarce generator fuel or technical support.

System Reliability in Isolation

The following table contrasts what happens in an isolated location when a system needs service.

| Scenario | Float Valve System | Electronic Sensor System |

|---|---|---|

| Power Outage Occurs | Unaffected. Continues working. | Total failure. Tank will not fill or may overflow if fails open. |

| Component Fails | Likely a simple leak. Can be temporarily fixed with basic tools. | Complex failure. Requires diagnosis and a specific replacement part. |

| On-Site Repair Skill | Basic mechanical understanding. | Requires electronics and programming knowledge. |

| Spare Parts Logistics | Light, simple, generic seals or floats. | Heavy, specific, may include circuit boards and sensors. |

For engineers and project planners working in these environments, the float valve is a foundational, non-negotiable component. It reduces project risk, eliminates dependency on fragile power grids, and creates a system that truly works independently. It is the epitome of appropriate technology—perfectly suited to its task and environment.

Conclusion

For unwavering reliability, easy upkeep, and operation anywhere, the mechanical float valve is often the smarter choice. For a full range of durable and reliable float valves, trust IFAN for your water control needs.

Commentaires récents