I once saw a project delayed because a cross fitting failed under unexpected pressure surge. This moment made me deeply analyze what it truly takes for these critical components to perform reliably.

Yes, a standard industrial brass cross fitting is specifically designed to handle high pressure from all four ports simultaneously. Its robust, solid-body construction and precise machining distribute internal forces evenly. However, the exact pressure limit depends on its size, thread standard, and material grade, and it is crucial to select a fitting rated for your system’s maximum operating pressure.

Understanding the limits and engineering behind these fittings is key to preventing system failure. Let’s break down the factors that determine their performance under pressure.

What is the Pressure Rating of a Standard Industrial Brass Cross Fitting?

Finding a clear pressure rating can be confusing. I often help clients decode specifications to match the fitting to their system’s demands.

The pressure rating of a standard industrial brass cross fitting typically ranges from 150 PSI to 600 PSI (10 to 40 BAR) for water and oil applications. This rating is not a single number but depends heavily on the thread type (e.g., NPT, BSP), the specific alloy used (like CW614N), and the operating temperature. Always check the manufacturer’s certified test data for the exact rating.

Understanding Pressure Rating Variables

You cannot simply say “all brass crosses handle X pressure.” The rating is a result of several interconnected factors. First, the brass alloy itself is important. Common industrial brass, like CW614N (also known as CDA 377), offers an excellent balance of strength, corrosion resistance, and machinability. Its inherent strength forms the baseline for pressure containment.

Next, the thread standard has a major impact. Tapered threads like NPT (National Pipe Tapered) create a metal-to-metal seal that wedges tighter under pressure, which can support higher ratings. Parallel threads like BSPP (British Standard Pipe Parallel) rely more on a sealing washer or O-ring and may have different pressure limits. The manufacturer designs and tests the fitting for a specific thread type.

The Role of Size and Temperature

Size matters greatly. A smaller fitting, like a 1/4″ cross, will generally have a much higher pressure rating than a 2″ cross of the same design. This is because the internal surface area facing the pressure is smaller, resulting in lower total force exerted on the fitting body. As the size increases, the wall thickness is also increased to compensate, but the overall pressure rating usually decreases.

Temperature is a critical but often overlooked factor. The pressure rating provided is usually for room temperature (around 20°C or 68°F). As the temperature of the medium increases, the strength of the brass decreases. For example, a fitting rated for 600 PSI at 20°C might only be safe for 400 PSI at 150°C. A good manufacturer provides derating charts.

Industry Standard Pressure Ratings

The table below provides a general reference for standard brass cross fittings with NPT threads at room temperature. This is for guidance only; always confirm with actual product specifications.

| Nominal Size | Typical Working Pressure (Water/Oil) | Common Material Standard |

|---|---|---|

| 1/4″ to 1/2″ | 500 – 600 PSI (34 – 40 BAR) | ASTM B16 / CW614N |

| 3/4″ to 1″ | 300 – 400 PSI (20 – 27 BAR) | ASTM B16 / CW614N |

| 1-1/4″ to 2″ | 150 – 300 PSI (10 – 20 BAR) | ASTM B16 / CW614N |

In summary, you must know your system’s maximum operating pressure, medium, and temperature. Then, select a fitting where the manufacturer’s published rating exceeds your requirements with a safe margin. Never guess with pressure ratings.

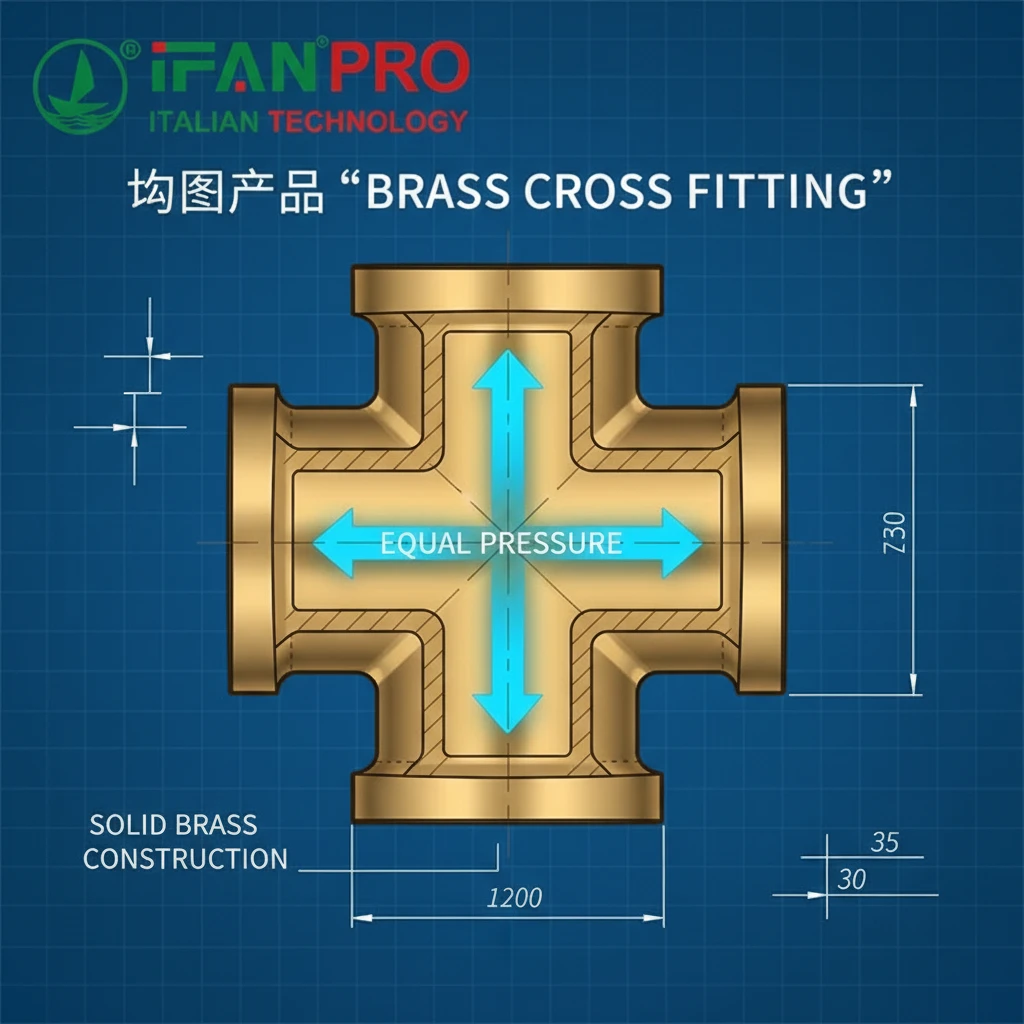

How Does Its Solid-Body Design Withstand Equal Pressure from All Directions?

The symmetry of a cross fitting is its greatest strength. I explain this using the principle of balanced forces, which is key to its reliability.

The solid-body design withstands equal pressure from all directions by distributing internal stress evenly throughout its monolithic structure. When pressure is equal in all four ports, the opposing forces cancel each other out, putting the body into a state of balanced compression. This eliminates bending or twisting forces that could weaken a less robust design.

The Principle of Balanced Forces

Imagine a sealed container under pressure—the stress pushes outward evenly on all walls. A well-machined brass cross fitting acts like a compact, pressurized vessel at its center. When all four ports experience the same pressure, the force pushing inward from one port is directly counteracted by the force pushing inward from the opposite port. This creates a state of equilibrium.

The solid-block construction is crucial here. Unlike fittings assembled from multiple pieces, a solid-body cross is machined from a single piece of brass bar stock. This means there are no seams, welds, or joints in the central body that could be potential failure points under stress. The material integrity is continuous.

Stress Distribution and Material Strength

The internal pressure creates tensile stress (a stretching force) within the walls of the fitting. The thick walls and generous radii (rounded corners) at the intersections of the ports are not just for looks; they are critical engineering features. Sharp corners concentrate stress, making them prone to cracking. The smooth, radiused corners in a quality fitting allow stress to flow smoothly through the material, distributing it over a larger area and preventing concentration.

Furthermore, brass is an excellent choice because it is a ductile material. Under high pressure, it has a slight ability to deform elastically (spring back) rather than crack suddenly like a more brittle material. This provides a small margin of safety against pressure spikes or water hammer.

Design Comparison: Solid Body vs. Alternative

Consider a weaker design, such as a cross made by soldering four separate tubes together. Under equal pressure, the stress would concentrate at the soldered joints. More importantly, if pressure were slightly uneven or if there were external pipe strain, the joints would be subject to bending moments, leading to rapid fatigue and failure.

The solid-body design inherently resists this. Its stiffness and one-piece nature ensure that any external loads from pipe misalignment are borne by the entire fitting, not just a single joint. This makes it uniquely suited for rigid, high-pressure systems where reliability is paramount.

Are There Reinforced Cross Fittings for Extra-High Pressure Applications?

Standard fittings have limits. When clients approach these limits, we must look for engineered solutions, not just hope for the best.

Yes, reinforced cross fittings for extra-high pressure applications do exist. These are often characterized by a hex-shaped or enlarged central body, thicker walls, and are sometimes manufactured from high-strength forged brass or even stainless steel. They are designed and tested to meet stringent standards like SAE J514 for hydraulic applications, with ratings exceeding 10,000 PSI in some sizes.

Identifying Reinforced Designs

When your system pressure exceeds the capability of a standard plumbing-grade cross, you need to step into the realm of hydraulic or instrumentation fittings. The most visible difference is the body shape. While a standard cross has a relatively slim, rounded body, a reinforced version will have a pronounced hexagonal central section. This hex body serves two purposes: it provides much more material to resist internal bursting forces, and it allows for easy installation and holding with a wrench without damaging the fitting.

The manufacturing process also changes. For the highest strengths, these fittings are not machined from bar stock but are forged. Forging aligns the metal’s grain structure and eliminates porosity, resulting in superior mechanical properties and impact resistance compared to cast or machined parts.

Material and Specification Upgrades

The material itself may be upgraded. While standard brass is common, a high-strength brass alloy or even stainless steel (like 316 stainless) is used for the most demanding conditions, especially when corrosion resistance is also critical. The threads are precision-cut to tighter tolerances to ensure perfect engagement and sealing under extreme force.

These fittings conform to specific performance standards. The most common is the SAE J514 standard for hydraulic tube fittings. A fitting marked under this standard has been rigorously tested for burst pressure, impulse fatigue, and corrosion. You don’t just get a pressure rating; you get a guarantee of performance under cyclic loading, which is common in hydraulic systems.

Selection Guide for High-Pressure Applications

Choosing the right fitting requires careful cross-referencing of your needs with product specs. Here is a basic guide:

| Application Pressure Range | Recommended Fitting Type | Key Features & Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Up to 600 PSI | Standard Commercial Brass Cross | Machined from CW614N, NPT/BSP threads. Suitable for water, air, oil. |

| 600 PSI to 3,000 PSI | Industrial Forged Brass Cross | Hex-body, forged construction, SAE J514 or similar. Used in industrial hydraulics. |

| 3,000 PSI to 10,000 PSI+ | High-Pressure Steel/Stainless Cross | Forged steel body, O-ring face seal or bite-type fittings (SAE J1453). For hydraulic and instrumentation. |

The key takeaway is never to push a standard fitting beyond its rating. If your design pressure is high, start your search with fittings designed and labeled for hydraulic or high-pressure service from the outset. The cost is higher, but it is insignificant compared to the cost of a system failure.

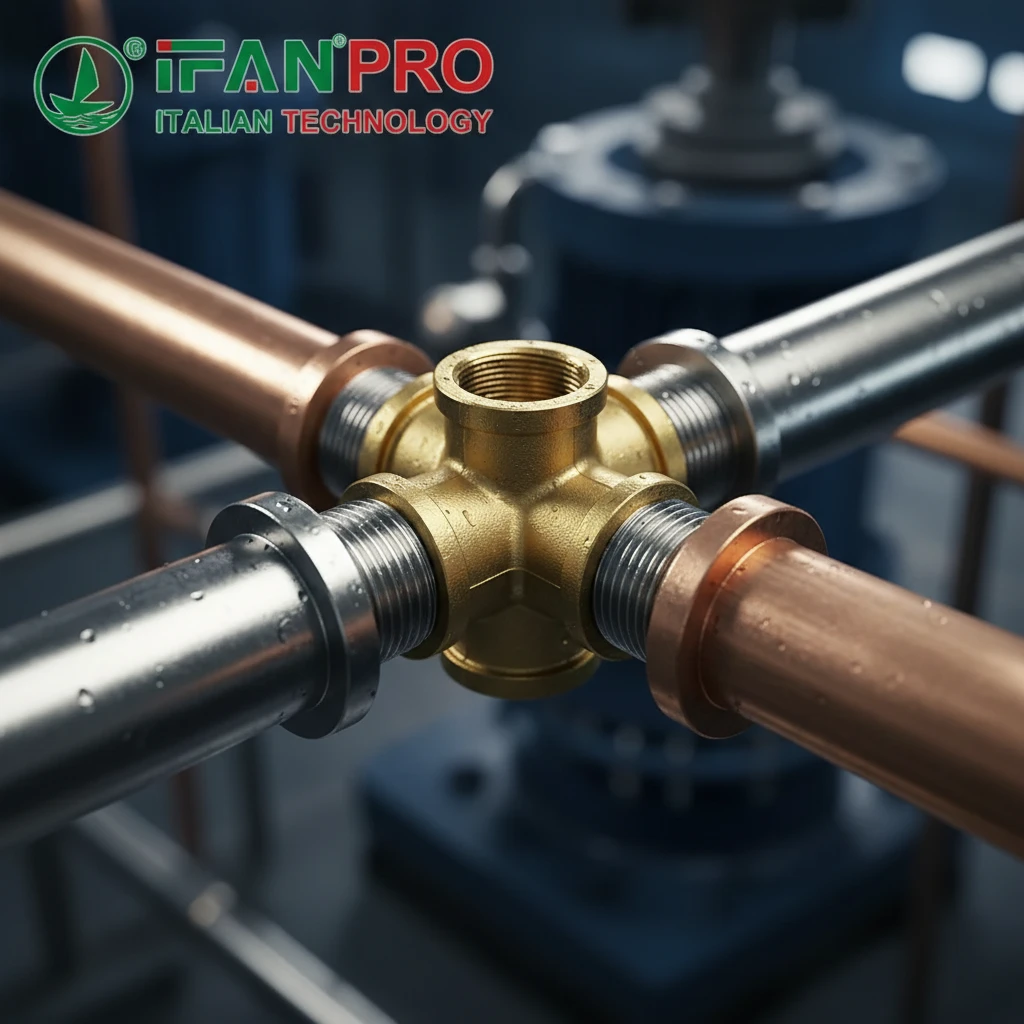

How Does Pressure Affect the Sealing Integrity at Each Threaded Port?

Pressure doesn’t just test the fitting’s body; it challenges every seal. A system is only as strong as its weakest leak path.

Pressure directly challenges sealing integrity by trying to force the medium through the microscopic paths between the threads. For tapered threads (NPT), higher pressure helps wedge the male thread tighter into the female port, improving the metal-to-metal seal. For all types, proper sealant (tape, paste) or a gasket is essential to fill these gaps and create a pressure-tight barrier that withstands vibration and thermal cycles.

The Mechanics of Thread Sealing

Threads are not perfect seals on their own. They are a mechanical locking device with spiral leak paths. The role of a sealant or a gasket is to block these paths. Under pressure, the fluid or gas will seek any available escape.

With NPT (tapered) threads, the seal is created by the interference fit between the male and female tapers. As you tighten the fitting, the threads deform slightly against each other. When system pressure increases, it acts on the backside of the threads, pushing them even tighter together. This is why a properly made NPT joint can become more secure as pressure rises. However, over-tightening can strip threads or crack the fitting, creating a leak instead of preventing one.

Sealant Function and Failure Modes

The sealant’s job is critical. Pipe thread sealant (paste or tape) fills the void spaces between the threads, hardens to prevent loosening from vibration, and provides lubrication for proper tightening. Under pressure, a good sealant will not extrude or wash out. If the sealant is insufficient, of low quality, or improperly applied, pressure will find these weak spots and initiate a leak, often starting as a small weep and growing over time.

For BSPP (parallel) threads, the sealing mechanism is different. The threads themselves do not seal. Instead, sealing is achieved by compressing a flat washer (for water) or an O-ring (for hydraulics) against a machined face inside the female port. Here, pressure actually helps by pushing the washer/O-ring tighter against the sealing surface. The integrity depends entirely on the quality and condition of that soft seal.

Factors That Compromise Sealing Under Pressure

Several factors can cause a sealed joint to fail under pressure:

- Vibration: Constant shaking can loosen threaded connections, breaking the sealant’s bond or allowing the threads to back off slightly.

- Thermal Cycling: Heating and cooling cause the brass and the connected pipes (often steel) to expand and contract at different rates. This movement can break the sealant’s grip.

- Over-tightening: This can gall the brass threads (causing metal-to-metal welding and tearing) or cause hairline cracks in the fitting body, especially at the port entries.

- Chemical Compatibility: The wrong sealant can be degraded by the system medium (e.g., certain oils), losing its sealing properties.

Best Practices for Pressure-Tight Seals

To ensure integrity, follow a disciplined process: First, ensure threads are clean and undamaged. Apply the correct sealant evenly, avoiding the first two threads to prevent contamination inside the pipe. Tighten to the proper torque—usually hand-tight plus 1.5 to 2.5 turns with a wrench. For critical high-pressure systems, consider using fittings with integral O-rings or metal face seals, which offer more reliable and reusable sealing performance than thread sealants alone.

Conclusion

A brass cross fitting can reliably handle multi-directional high pressure when its rating, solid-body design, and sealing are correctly matched to the system. For guaranteed performance in standard and demanding applications, specify IFAN’s range of precision-machined and forged brass cross fittings.

Recent Comments